The rainbow diet pills: there and back again

* This post contains spoilers for Requiem for a Dream.

Last night I re-watched Requiem for a Dream, a Darren Aronofsky masterpiece that is perhaps the most gut-wrenching, emotional rollercoaster of a movie ever made in cinematic history. Requiem tells the story of four people descending into addiction, eventually sacrificing their bodies, minds and dignity for their drug-of-choice.

A particularly harrowing narrative is that of Sarah Goldfarb, an elderly woman who begins taking colourful diet pills throughout the day to slim down for a potential appearance on TV and “be somebody”. Her wishes were never fulfilled – instead she is consumed by hallucinations and delusions. Her story ends with a torturous scene in which she is subjected – without anesthesia – to ECT (electroconvulsive therapy).

A lot can be said about the movie. But this time around, one question peeked my interest: is Sarah’s addiction story based on historical facts? What were diet pills like back in the 1970s? Although the movie never discloses what the pills contain, we can make a few rational assumptions based on their effects: they send Sarah into a frenzy of activity, increases her body temperature, triggers jaw-clenching and kills her appetite. Amphetamines certainly fit the bill, but they are far, far from the whole story.

Sarah getting hooked on diet pills. Source: celebratingcinema.blogspot.com

Dangerous colours

First introduced in the 1950s, amphetamines quickly gained popularity for their strong appetite suppression effects. Phentermine, an amphetamine derivative still on the market today, was approved by the FDA in 1959 and hailed as “mother’s little helper” for their energy-boosting effects. Obetrol, a pill popular in the 1960s and later reformulated as Adderall, contained a toxic mix of amphetamine (speed), methamphetamine (meth) and dextroamphetamine(dex) salts bound to get you higher than the sky. Amphetamines generated considerable interest among physicians eager to capitalize on their actions. There was only one problem: people didn’t like being “tweaked out” at the end of the day.

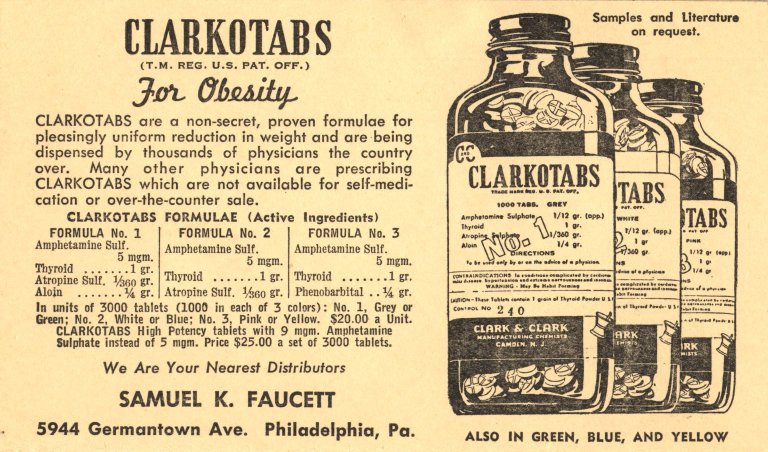

The solution was simple and terrifying. Drug companies began formulating combination diet pills, which included amphetamines, diuretics, laxatives and thyroid hormones to send the body into weight-loss overdrive, as well as benzodiazepines, barbiturates, corticosteroids and antidepressants to deal with nuances like insomnia and anxiety (see Table below). These uppers and downers came in brightly colored capsules and tablets, and the regime was given the innocuous, hopeful-sounding name the “rainbow diet pills”.

Between the 1950s and 70s, a slew of small firms sprung up to directly market rainbow pills to physicians – particularly to those unbound by ethics and eager for some extra dough. The businesses built up a façade of personalized medicine, purposefully manufactured pills with dozens of colours to ensure that each patient would receive his or her own combination of coloured pills. Their marketing tactics worked. By 1967, weight loss clinics were pulling in $250 million each year in patient fees, with an additional $120 million on rainbow pills alone. As any first year pharmacist (or seasoned drug user) can tell you: mixing uppers with downers is a very, very bad idea. (Think pharmaceutical grade speedball.) Before the turn of the decade, over 60 deaths and severe adverse effects prompted the FDA to mass seize the pills from the manufacturers and tighten regulatory control of amphetamine-based medications. The industry withdrew into the shadows, but the damage was done.

Clarkotabs: one of the first combination diet pill formulations. Source: http://ihm2.nlm.nih.gov/

Tolerance to amphetamines builds up fast. Chronic use lowers the drugs’ efficacy, and an uneducated patient may believe that they had stopped working altogether. And herein lies the danger. Although each pill generally contained a relatively safe dose of a particular drug, some patients resorted to stacking pills to speed up or restart weight loss – sometimes taking up to 4 times the suggested amount. Worse still is the combination. Thyroid hormones alone can trigger heart palpitations. Diuretics and laxatives deplete the body of potassium, an electrolyte that’s crucial for keeping the heart beating at a normal rhythm. Add in a hefty dose of digitalis or ephedrine – both herbal compounds that promote weight loss – and normal heartbeats are reduced to useless quivers. A 1967 article in Times magazine reported the deaths of at least 6 Oregon women who overdosed on rainbow pills. The toxic combination had stopped their hearts, and they died alone.

Speedy psychosis

In Requiem, Sarah descended into madness after repeatedly stacking her upper pills. In one jarring scene, she watched in horror as her younger self apparated out of her TV set and into the living room, whereby young Sarah cruelly laughed at the antiquated fixtures and mocked her living conditions.

Chronic, high-dose consumption of amphetamine derivatives are known to trigger psychosis similar to that in schizophrenia: paranoia, delusions, as well as auditory and visual hallucinations. Historically these side effects were thought to be associated with methamphetamine abuse, not prescription rainbow pills. The earliest sign of trouble came from a 1964 case report, which documented the mental breakdown of a 26-year old woman after consuming phentermine – the most popular amphetamine used for diet control and weight loss. Similar stories are littered across the medical literature spanning decades. In 1977, after one month of taking phentermine, a 20-year old woman became distraught, stating intense feelings of déjà vu and was convinced that her mother and college classmates were out to get her. In another case reported in 2005, a 30-year-old woman took Xenadrine (an OTC weight-loss supplement) and phentermine purchased over the internet, and within 3 weeks developed delusions of men stalking her. The woman’s symptoms improved after replacing diet pills with anti-psychotics, but came back with a vengeance once she restarted her Xenadrine/phentermine combo. Neither woman had any family history of psychiatric disorders, nor had they previously experienced any psychotic episodes prior the use of diet pills.

Despite numerous reports, no one has pooled existing data into a meta-analysis to try to pinpoint phentermine (or any other upper component of rainbow pills) as the psychosis-triggering agent. Even today physicians are still divided in the exact role of amphetamines in acute psychosis. Are the drugs precipitating psychotic episodes in those at risk for schizophrenia? Or can they cause psychosis in otherwise healthy individuals?

Care to guess what the bottles contain?

The rainbow pills return

After lurking in the shadows for over two decades, rainbows pills have reappeared on the market under the guise of herbal weight loss supplements. In 2005, the FDA confiscated thousands of bottles of imported herbal “fat burning” supplements adulterated with benzos, fenproperex (an amphetamine derivative) and the anti-depressant fluoxetine. One survey of rainbow pill takers in Massachusetts revealed at over two thirds experienced insomnia, anxiety or other adverse effects; another study from the Texas Poison Center Network found imported rainbow pills as the culprit for high blood pressure, vomiting and unnaturally rapid heart beat. Marketed with trendy labels like “all natural”, “herbal extract” and “organic”, these new generation combo diet pills are just as dangerous as their 1970s predecessors. Due to the 1994 Dietary Supplement Act, which states that dietary supplements do not require premarket review, the FDA is powerless to stop the pills from hitting store shelves in the first place. And thanks to the Internet, the distribution network of rainbow pills is larger than ever.

I set out to satisfy my curiosity of the 1970s diet pill scene, thinking that it must’ve been heavily dramatized in Requiem for a Dream. But in this case, reality is just as chilling.

Cohen PA, Goday A, & Swann JP (2012). The return of rainbow diet pills. American journal of public health, 102 (9), 1676-86 PMID: 22813089